Grand Central Dispatch in Swift

Grand Central Dispatch, or GCD for short, is a low-level C APIs for managing concurrent tasks. It helps us improve our app performance by executing a block of code in reasonable threads, like perform computationally expensive tasks in the background. GCD provides several options for running tasks such as synchronously, asynchronously, after a certain delay, etc.

In this post I will explain more details about GCD and how it works, also provide some interesting points when we work with GCD. Let’s start.

Introduction

At the heart of GCD are dispatch queues which are pools of threads managed by GCD. Apple creates GCD to make developers don’t need to care too much about these queues, they just simply dispatch a block of code to a given queue without caring about which thread is used.

GCD Concepts

Concurrency

Concurrency is achieved when more than two tasks are executed at the same time. In fact, the word “Concurrency” does not exactly mean “at the same time” or “happen in parallel”. Under the hook, CPU gives every task a certain time slice to do its works. For example, if there are 5 tasks to be executed in one second, with the same priority, the OS will divide 1,000 milliseconds by 5 (tasks) and will give each task 200 milliseconds of the CPU time. As a result, they will appear to have been executed concurrently.

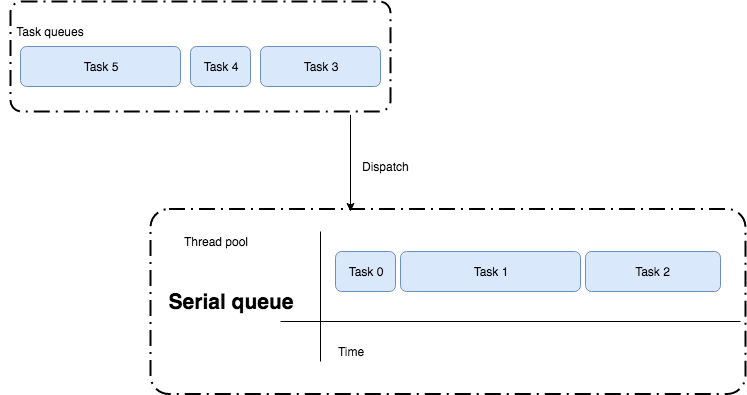

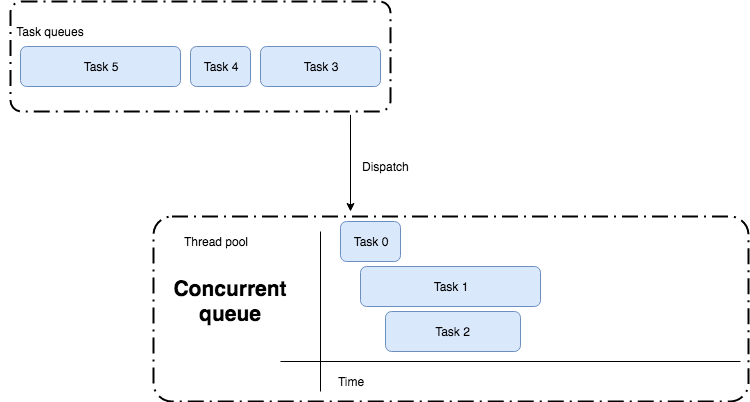

Serial queue and concurrent queue

A serial queue will execute its tasks in a first-in-first-out (FIFO) fashion. It’s mean that they can only execute one block of code at a time. They do not run on the main thread, therefore, they do not block the UI.

In contrast, a concurrent queue allows to execute multiple tasks in parallel. It means tasks can finish in any order and you won’t know the time it will take.

Synchronously (sync) and asynchronously (async) methods

When you dispatch a task to a queue, you determine whether the block run synchronously or asynchronously. There are some main differences between the two techniques:

- A synchronous method returns control to the caller only after the task is completed whereas an asynchronous method returns control to the caller immediately.

- Since asynchronous methods return control immediately so they don’t block the current thread.

- Note that the world “synchronous” does not mean the program have to wait for the code to finish before continuing. It just means that the concurrent queue will wait until the task has finished before it executes the next block of code on the queue.

The code below demonstrates how to use async and sync executions.Generally, we can not predict the output when we run the code above because everytime we run the program, the numerous of different outputs will be printed. We can only say that “B” will always be printed after “A” as the caller need to wait for the block [1] returns control so that it can execute the next block [2].1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17DispatchQueue.global().sync { [1]

print("A")

DispatchQueue.global().async {

for i in 0...5 {

print(i)

}

}

}

DispatchQueue.global().sync { [2]

print("B")

DispatchQueue.global().async {

for i in 6...10 {

print(i)

}

}

}

If we edit these inner blocks tosync, we guarantee that the output will always beA 0 1 2 3 4 5 B 6 7 8 9 10.Three main types of queues

There are three main types of queues in GCD: - Main queue: Tasks are dispatched to this queue will be performed on the main thread, where UI-related works are called. The Main queue is a serial queue.

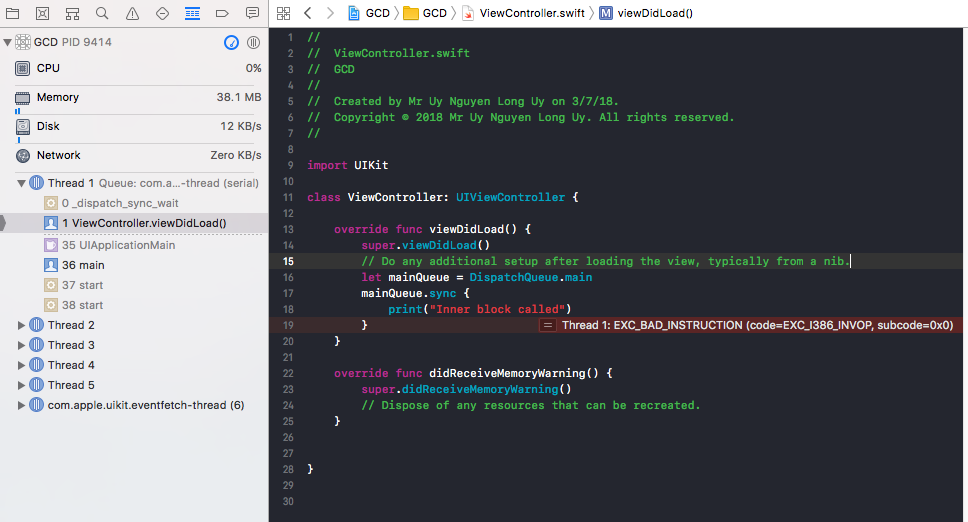

Important note, the sync method can not be called on main thread because it will block the thread completely and lead the application to deadlock. Therefore, all tasks submitted to the main queue must be submitted asynchronously.

1 | override func viewDidLoad() { |

- Global queues: They are concurrent queues and are shared by the system. We use global queues for any task that does not involve the UI. For example, downloading an image from the internet then display it to the user after it is downloaded, fetching database from a server, etc.

When we work with global queues, we don’t specify the priority but we use a Quality of Service (QoS) to help the GCD determine the priority of the tasks. It is important to keep in mind that apps use various resources like CPU, memory, network interface, etc. Thus, we should choose the right QoS of the queue in order to remain responsive and efficient of the app. The OS will base on the given QoS to make smart decisions about when and where to execute them.

There are four types of QoS: - User-interactive: This indicates that the tasks need to be executed immediately in order to remain responsive on UI. We use it for UI updates or performing animations.

- User-initiated: Work that the user has initiated and requires immediate results (In a few seconds or less). We use it to perform an action when users click something in the UI.

- Utility: the tasks may take some time to complete and does not require an immediate result (Takes a few seconds to a few minutes) such as downloading data.

- Background: This represents tasks that the user is not directly aware of. Normally, we use it for fetching data or any tasks that don’t require user interaction.

- Custom queues: When you create a custom queue, you can specify which type of queue it is (Serial or concurrent). By default, they’re serial queues.

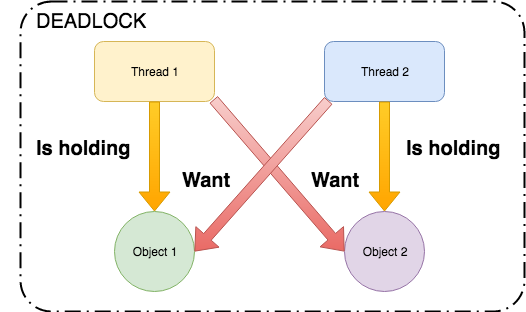

Deadlock

The word Deadlock refers to a situation in which a set of different threads sharing the same resource are waiting for each other release the resource to finish its tasks.

When working with the GCD, if we do not fully understand the GCD’s concepts, we may create a deadlock in our code. For example, the code below is making a deadlock.

1 | func deadLock() { |

First, we create a custom queue with a given label. Then we dispatch asynchronously a block of code calling another block of code synchronously. It is clear that the inner and the outer blocks are executing on the same queue. By default, a custom queue is serial so the inner block will not start before the outer block finishes. On the other hand, the outer block can not finish because the inner block is holding the control of the current thread (Synchronously). Hence, a deadlock occurs.

There are two ways to fix the problem. The first one is changing the type of the queue to concurrent. By doing this way, we ensure that the inner block does not have to wait for the outer block has finished so that it can start.

1 | let myQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "myLabel", attributes: .concurrent) |

The second one is changing the inner block to async. This time, the outer block will not wait for the inner block has completed so that it can start.

1 | myQueue.async { |

There is a recommend on Apple document about Deadlock at Dispatch queues and thread safety chapter"Do not call the dispatch_sync function from a task that is executing on the same queue that you pass to your function call. Doing so will deadlock the queue.

If you need to dispatch to the current queue, do so asynchronously using the dispatch_async function."

Livelock

There is another lock concept besides deadlock called Livelock. Unlike deadlock, the livelock does not block the current thread. They’re just unable to make further progress. Or to more accurately, livelock is “a situation in which two or more processes continuously change their states in response to changes in the other process(es) without doing any useful work”.

There is a good human example of livelock on StackOverflowA husband and wife are trying to eat soup, but only have one spoon between them. Each spouse is too polite, and will pass the spoon if the other has not yet eaten.

There are other types of lock when we work with concurrency like bound resources, mutual exclusion, starvation. Because of the scope of this post, I will not explain all of them here. Please refer to other sources for more details.

Important notes

- On iPhones, discretionary and background operations, including networking, are paused when Low Power Mode is enabled.

- When using Xcode 9 with iOS 11, a warning will be emitted when a user-interface object is accessed from a non-main thread.

- The user interactive priority should be rare in your program. If everything is high priority, nothing is.

Conclusion

In this post, I showed you some interesting points about GCD in Swift. In next post, we will discuss more about other advanced concepts of concurrent programming like DispatchGroup, Operation Queue, Group Tasks, etc. Then we will implement a tiny project to mix them together.

If you have any comments, don’t be hesitate to contact me.

References

[1] Apple’s documentation: Concurrency Programming Guide

[2] iOS 8 Swift Programming Cookbook by O’Reilly, Chap.7: Concurrency and Multitasking.